Nearly two-thirds of hate crimes go unreported to law enforcement.

How to Report a Hate Incident

occured in the U.S. in 2015.

In the same year only 5,850 hate crimes

were reported by local law enforcement agencies.

Hate crimes and hate incidents are notoriously underreported. Campus and community leaders may be reluctant to report incidents for public affairs reasons, and those targeted by hate may not be comfortable doing so. However, for hate crimes to be most effectively addressed, an accurate public record is imperative.

- Contact campus police or local police, depending on the location of the crime. If you are in need of emergency services call 911 (9911 on many campus telephones). If you are not comfortable going to law enforcement, find a trusted intermediary like a counselor, staff member, or campus organization.

- Report the incident. Each campus has designated procedures for reporting hate crimes and incidents of harassment and intolerance posted on the college website. Some campuses provide reporting forms online. If you are unsure how to report an incident to your campus, the Title IX office is a good starting point.

- If you are reluctant to go to law enforcement, find a student or campus group that can be an intermediary in reporting the attack. Examples include: Office of Diversity and Inclusion; groups representing those who may be targeted, including Black, Latino, Asian, Native American, or LGBTQ student associations; or disability rights groups on campus.

- When reporting, provide all details of the crime or incident you recorded or remember, including: the perpetrator’s(s’) gender, age, height, race, weight, clothes, or other distinguishing characteristics. If any threats or biased comments were made, such as racial slurs or anti-gay epithets, include them in the report, as well as any damage to property.

- If you believe the incident was bias-motivated, urge the officer to check off the “hate/bias-motivation” or “hate crime/incident” box on the police report.

- In addition to contacting your local law enforcement agency, also contact your local FBI field office and provide the same information. Further information on how to report these crimes can be found on the FBI’s Hate Crime website.

The Problem of Hate on Campus

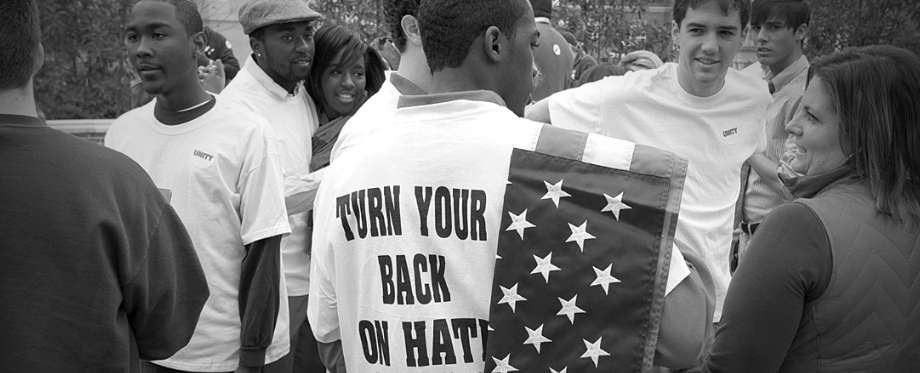

Rally against hate, University of Minnesota campus, October 6, 2016. Photo by Flickr user Fibonacci Blue

Hate incidents have been surging across the country, and colleges and universities are not exempt from the increase. Nooses and racist graffiti found on campuses, hateful flyers posted in common areas, and rallies that promote hatred – these incidents seek to provoke fear and division. Students, administrators, faculty, and campus police can counter hate on campus with visible and tangible actions, while respecting the First Amendment right to free speech.

were reported on college campuses in the ten days after the 2016 Presidential Election.

Addressing Hate: Preventing and Responding to Hate on Campus

The College of Marin, California, campus community participated in a regional United Against Hate campaign.

Hate doesn’t happen in a vacuum, and for far too many communities, it is not new. While to some, incidents may appear isolated, hate incidents can be a symptom of deeper systematic issues. To create a campus environment where students of diverse backgrounds and identities are safe to learn, it is important that Administrators not just react when an incident occurs, but take proactive steps to identify policies and practices that may perpetuate systemic discrimination and to prevent future hate incidents.

Proactive Steps Campuses Can Take To Prevent Hate on Campus:

- Have a dedicated multicultural center that can serve as a sanctuary to all students.

- Review student body and faculty diversity to ensure the campus represents a critical mass of traditionally underrepresented communities.

- Do not ignore painful campus history. Instead provide opportunities for open discussions and historic context. Involve students in discussions.

- Hold regular forums with students to listen to their concerns and work with them to create plans to respond to the issues raised.

Responding to a Hate Incident on Campus:

- Ensure the student body is and feels safe.

- Hold open forums that center the experiences of individuals directly affected by the incident. (E.g. A discussion of racist graffiti in public space can easily turn to general issues of public safety and vandalism. Do not distract from the incident or use the forum to discuss alternative issues. Focus on the incident at hand.)

- Hate incidents can be traumatic for those affected. Listen to their needs. Do not ask or expect individuals directly affected to lead campus forums on the incident.

- Offer mental health services that are accessible to all communities.

For more than a decade, college students have created Not On Our Campus campaigns that address safety and inclusion, including issues of racism, anti-Semitism, LGBTQ bias, and hazing. Here you will find videos and stories that document campus efforts + resources to get you started.

Stand up on your campus!

The Not On Our Campus (NOOC) Quick Start Guide provides a step-by-step plan to launch your NOOC Campaign.

Find more college resources to build safe, inclusive campus communities.

To learn how you can get involved, contact the Not On Our Campus team at info@niot.org.