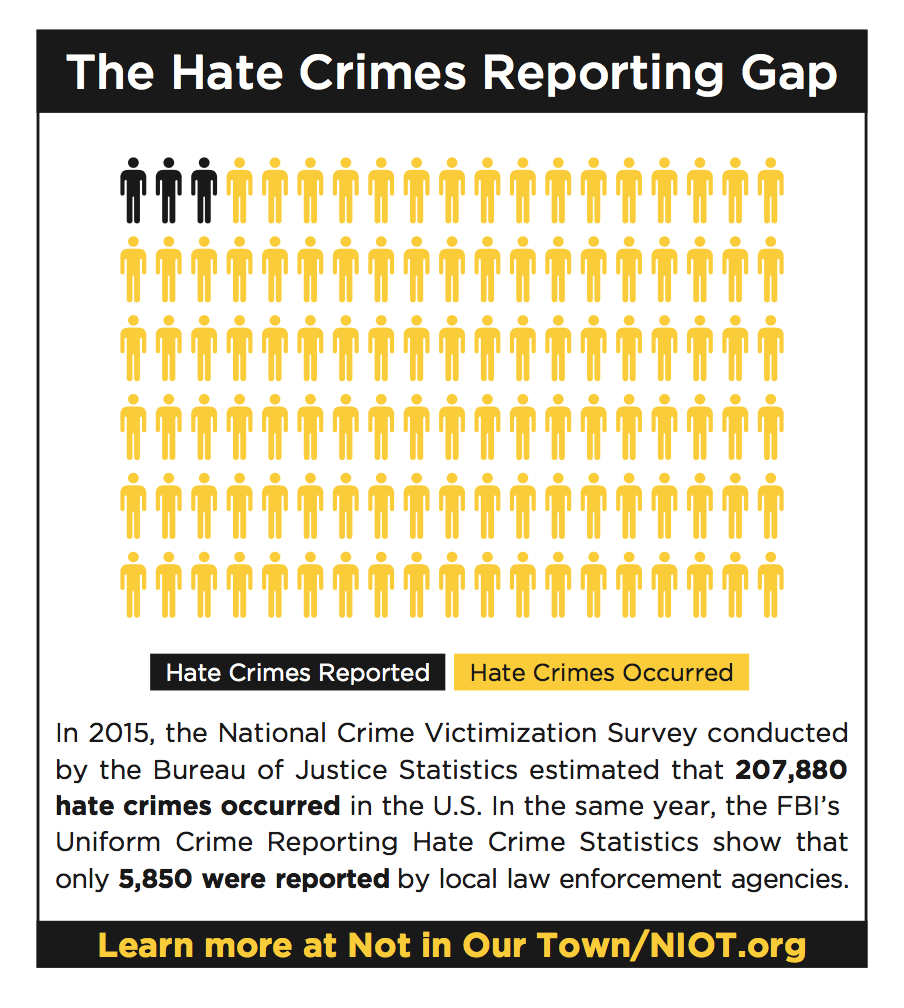

In 2016, 13,478 law enforcement agencies (88% of agencies participating) either did not report or reported zero hate crimes to the FBI.

Reporting a Hate Crime

Oak Creek Police Chief John Edwards recalls the attack on August 5, 2012 at the Sikh Temple of Wisconsin.

The message of a hate crime is that “people like you” are not welcome or safe here. Physical assaults, acts of vandalism, and threats of violence can send shockwaves of fear and uncertainty through targeted communities. When law enforcement commits to accurately reporting and consistently responding to hate crimes and bias incidents, it can: demonstrate support for victims and all members of the community; increase public safety; and help prevent future hate crimes.

Hate crimes targeted at people based on their perceived race, color, national origin, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, religion, and/or disability are a widespread problem in communities across the United States – but an acute discrepancy exists between the number of actual hate crimes committed, and the number officially reported to the FBI.

This Hate Crimes Reporting Gap presents formidable challenges for law enforcement, including:

- Hate and bias crimes can escalate if not identified, addressed, and tracked;

- Without accurate data, cities cannot allocate appropriate resources to address tensions and violence in communities; and

- Inadequate response to hate crimes can leave affected communities feeling unheard and unsafe.

Hate Crime: A criminal act motivated by hate or bias on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, religion, or disability.

The Seattle Police Department’s Bias/Hate Crime Data

The Seattle Police Department provides bias/hate crime and incident data to the public as part of the agency’s online crime dashboard. SPD’s Bias Crimes coordinator tracks this statistical data as part of her full-time role in the Bias Crimes Unit, which is located within the Violent Crimes section.

Within law enforcement agencies, some of the factors related to underreporting are:

- UCR reporting to the federal government is voluntary.

- Public officials may fear increased numbers reflect poorly on the community.

- Officers and prosecutors may need training to identify, investigate, and accurately report hate crimes and bias incidents.

To overcome these obstacles, law enforcement agencies should:

- Establish a culture, from top leadership to rank-and-file, that prioritizes clear, decisive response to hate crimes.

- Invest in quality training for new recruits and ongoing training for all department officers.

- Communicate to officers, investigators, and the public that increased reporting can not only bring justice to victims and communities, but it can also strengthen community trust in law enforcement.

San Diego County Regional Hate Crimes Procedure Manual

The Law Enforcement Training Subcommittee of the San Diego (California) Hate Crimes Community Working Group collaborated with experts from the state of California and incorporated materials from the US DOJ’s hate crimes training manuals and training curricula created by the California Peace Officers Standards and Training Hate Crimes Committees to develop a Hate Crimes Procedure Manual. The manual serves as a useful guide for agencies looking to develop or enhance policies and procedures for preventing and responding to hate crimes.

The manual features:

- Examples of hate crimes and hate incidents

- Suggested hate crime prevention activities

- Recommended reporting procedures

- Advice for supporting hate crime victims

- Best practices for first responders interviewing victims, witnesses, and suspects

- Guidance for evidence collection among other important information

Another area of concern is that most hate crimes are never reported to law enforcement in the first place.

Common reasons for this include:

- Communities targeted for hate may not feel safe or comfortable reporting hate crimes to law enforcement.

- Long-standing distrust among some communities leads victims to believe law enforcement will be unwilling or unable to help.

- Immigrant communities may fear deportation or other consequences if they step forward.

- Victims who speak different languages or have disabilities may not report due to cumbersome, inaccessible hate crime reporting procedures.

- Individuals and targeted communities may fear retaliation if they report incidents.

To build trust and help people feel safe reporting hate crimes and bias incidents, agencies should:

- Communicate to the public that you take hate crimes and bias incidents seriously.

- Demonstrate a consistent commitment to protecting all members of the community.

- Conduct outreach outside of crisis situations to develop positive relationships with diverse populations, and create partnerships with organizations that represent communities targeted for hate. Community outreach dialogues should address questions like, “In addition to making a 911 emergency call, who is the point of contact in this community to alert if there is a hate crime or bias incident?” and, “Who is the point of contact if a member of the community has a question about local law enforcement’s hate crime reporting practices, response, or prevention activities?”

- Create accessible and multilingual reporting procedures, and accept reports of bias incidents as well as hate crimes. Easy, transparent reporting procedures encourage victims and other residents to reach out after an incident.

- Conduct a public affairs campaign to publicize a telephone hotline and online information about reporting.

Hate Crime Data Collection Guidelines and Training Manual

Version 2.0

Dated: 2/27/2015

The FBI’s Criminal Justice Information Services (CJIS) Division, UCR Program developed this manual in consultation with civil rights organizations to help law enforcement agencies establish updated hate crime training programs. The publication includes excellent sample scenarios that are useful not only for purposes of effective data collection, but also to help understand what hate looks like in different communities.

Sample topics include:

- Legislative Mandate to Report Hate Crime

- Definitions for Hate Crime Data Collection

- Criteria of a Hate Crime

- Scenarios of Bias Motivation

- Submitting Hate Crime Data to the FBI UCR Program

- Working with Transgender Victims/Witnesses

- Special Considerations when Working with Victims from Arab, Hindu, Muslim, Sikh, and South Asian Communities.

The Problem of Hate in Communities

San Francisco District Attorney George Gascón and Assistant District Attorney Victor Hwang at a hate crimes press conference.

The fear and insecurity caused by hate crimes not only hurts targeted individuals, but also can negatively affect entire communities, driving decisions about where to live and work, or how often to participate in the community.

The response of law enforcement to hate incidents or hate crimes can strengthen the trust between community and law enforcement that is essential to public safety. Because of the unique ways in which hate crimes impact entire communities, if law enforcement does not respond effectively to hate incidents and hate crimes, it can significantly undermine trust.

Victims of Hate Crimes Need Support

One of the distinguishing features of hate crimes is that perpetrators target a victim because of their actual or perceived identity. Researchers have analyzed how hate crimes “hurt more” than non-bias motivated crimes, in part because bias-motivated crimes can inflict physical, mental, and emotional harm, and can affect behavior of victims. (Citation: Pezzella.) FBI 2016 hate crime statistics indicate that hate crimes are most often motivated by race, with religion and sexual orientation being the second and third most common motivations.

Another characteristic of many hate crimes is the extra degree of violence and cruelty not as common in, for instance, economic crimes. Even though a bias-motivated crime does not require extreme violence to cause fear within a vulnerable community, research has shown that attacks motivated by bias tend to be more violent than attacks that arise out of other circumstances. According to the 2017 BJS report, Hate Crime Victimization, 2004 – 2015:

Overall, about 90% of NCVS-reported hate crimes involved violence, and about 29% were serious violent crimes (rape or sexual assault, robbery, and aggravated assault). During 2011-15, violent crime accounted for a higher percentage of hate (90%) than nonhate (25%) crime victimizations. The majority of hate crimes were simple assaults (62%), followed by aggravated assault (18%), robbery (8%), and theft (7%).

For all of these reasons, law enforcement must be especially attentive to individuals targeted for hate crimes. Law enforcement, victim advocates, and prosecutors should make special efforts to connect with victims of hate crimes and targeted communities, recognizing that fear can permeate throughout communities.

"Victims of bias crimes tend to take twice as long to recover on an emotional level, because it’s a very personal attack upon them -- be it because of their skin color, sexual orientation, or religion. These crimes are message crimes, not just to that one victim. We really have an entire community that’s victimized when one person of a certain group is targeted because of who they are."

— San Diego County, CA Deputy District Attorney Oscar Garcia

It is Important to Document and Report Bias and to Investigate and Prosecute Hate Crimes

Because hate crimes can devastate entire communities, not only the individuals targeted, when hate crimes occur, it is important that they be recognized for what they are. This is why crimes motivated by bias should always be reported as hate crimes and why prosecution for hate crimes should be pursued wherever possible.

State hate crime laws provide authority to state and local law enforcement officials and prosecutors to investigate and prosecute hate crimes. Federal hate crimes laws provide authority to the FBI and federal prosecutors to investigate and prosecute hate crimes.

Hate Crime Statutes

Hate crime statutes generally fall within two categories, to either:

- create standalone criminal charges for hate crimes, or

- create penalty enhancements to existing crimes.

Statutes require the prosecutor to prove that an underlying bias against a person’s race, color, national origin, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, religion, or disability motivated the crime.

State Hate Crime Overviews

State hate crime laws vary significantly. The Stop Hate project has created an online resource detailing each state’s laws and relevant statutes.

From a legal standpoint, bias motivation is the key element of a hate crime. Every criminal statute that addresses hate crimes includes a central element of bias motivation. As a result, law enforcement officers need to look for what the FBI Hate Crime Data Collection Guidelines and Training Manual refers to as, “sufficient objective facts to lead a reasonable and prudent person to conclude that the offender’s actions were motivated, in whole or in part, by bias.” A law enforcement officer should look for and note “bias indicators,” or facts that suggest the possibility of a bias motive.

When this element is written into a criminal statute, it can make the crime more complicated to prove, and for this reason, some prosecutors are reluctant to charge perpetrators with hate crimes. However, a conviction under such statutes typically comes with harsher penalties. Prosecutors should bring hate crime charges where the evidence and the available statutes make this possible. Convictions under these statutes send an important message to targeted communities and to would-be perpetrators that the larger community is stronger than hate.

When law enforcement and public officials recognize an act of hate for what it is, they acknowledge and validate the experience of the victim and affirm the status of the victim as a full member of the community.

(adapted from A Prosecutor’s Stand: Important Facts for Law Enforcement Officers Leading Discussion of the Film, available online from the COPS Office.)

Community Stories: Why Confront Hate?

What leaders say and do can make all the difference in building resilience in the face of hate. These local examples demonstrate how law enforcement officials can help lead meaningful changes in their communities.

1) Location: Monmouth County, NJ

Bias crimes investigator Detective David D'Amico regularly visits schools to talk frankly and powerfully to the group responsible for the majority of these crimes—young people. His presentation includes cautionary advice not only about how derogatory words used online are hurtful, but how they can also make the user a target for recruitment by hate groups.

2) Location: San Francisco County, CA

San Francisco District Attorney George Gascón, in an interview with Not In Our Town Executive Producer Patrice O'Neill, discusses the importance of reporting, prosecuting, and preventing hate crimes.

3) Location: Patchogue, NY

Realizing that violent crimes were going unreported by the local immigrant community, Suffolk County Police Department Community Liaison Officer Lola Quesada pioneered an innovative Spanish language training program for new recruits to encourage communication and cultural understanding.

4) Location: Elk Grove, CA

When two elderly Sikh men are gunned down during their evening walk, community members, civic leaders and local law enforcement stand together against hate and intolerance. Elk Grove, CA Police Chief Robert Lehner talks about the importance of recognizing a hate crime in the absence of clear evidence.

who didn’t report the hate crime thought police could not or would not help, or would create problems for them.

“If a police chief doesn't take a visible and active role, then there is an assumption that everything is alright. And these hate groups have learned through experience that if a community doesn't respond, then the community accepts. Silence is acceptance to them.”

– Former Billings, MT Police Chief Wayne Inman