The following is a post from Jim Hennigan, a resident of Greenville County who supported instituting a Martin Luther King Day holiday in the county. After two decades, the Greenville County Council finally voted to officially adopt the holiday in 2004, making it the last county in the state of South Carolina to do so. In this post, Jim recalls the battle, the NIOT documentary that never got made and what it's like in Greenville today.

When is it time to call it a wrap on the set of a social justice campaign?

Probably never.

|

|

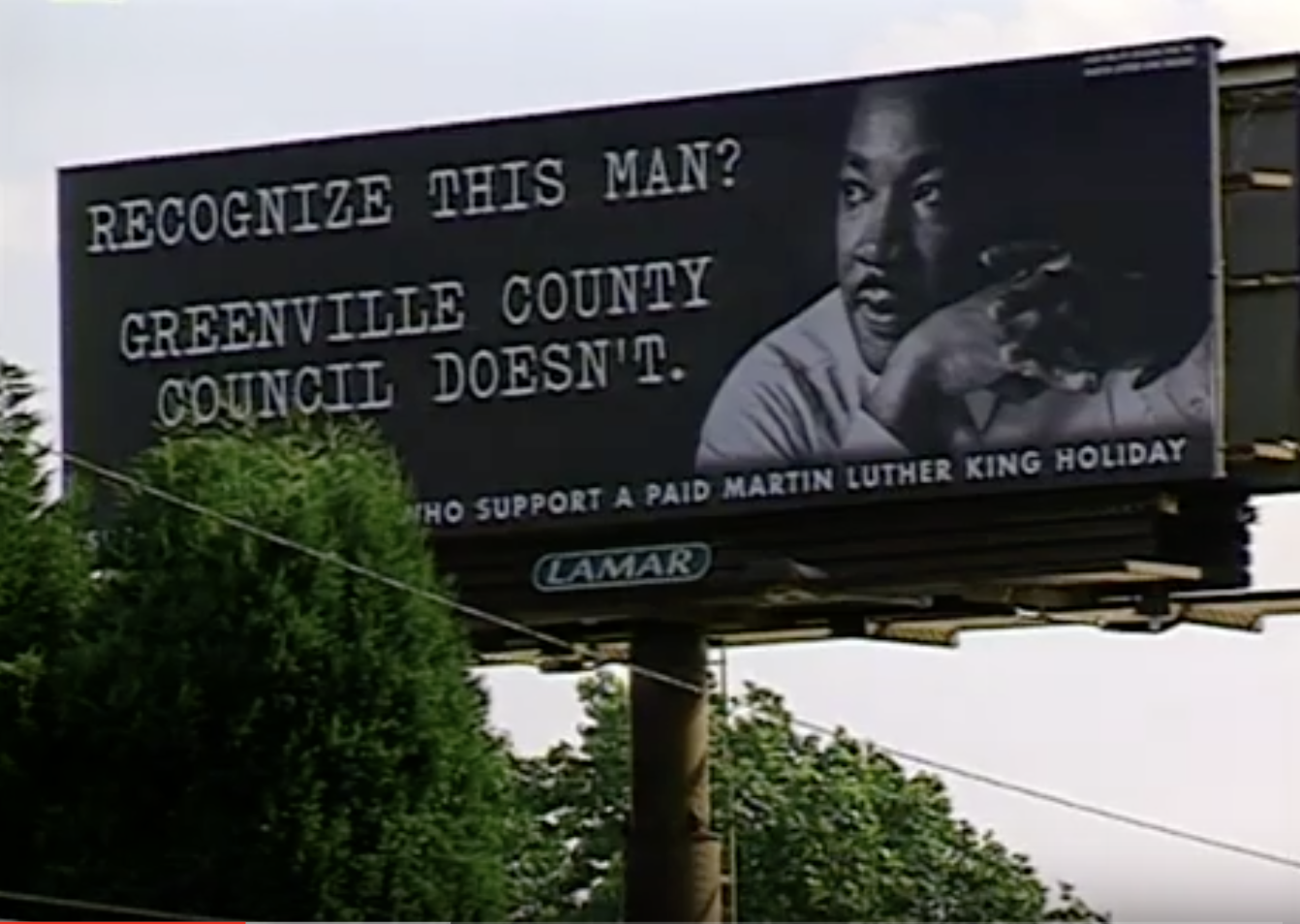

A sign by the side of the road paid for by community members who supported a Martin Luther King Jr. Holiday in Greenville County. (Credit: NIOT 'Holiday' film, 2003)

|

|

|

Greenville, SC

|

Here in Greenville, South Carolina, we are marking the 15th anniversary since our County Council made Greenville the last county in this Deep South state to officially recognize the Martin Luther King, Jr. Holiday. The holiday came to Greenville after a 20 year-long triathlon of feet dragging, pearl clutching and dubious rationalizing.

That’s par for the course.

Greenville also held out on enforcing the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education desegregation decision until 1970, when it exhausted all legal avenues to delay the inevitable.

When nine members of the Emanuel AME Church were massacred in Charleston in 2015, politicians on both sides of the aisle rallied to strike the Confederate battle flag that flew above the Statehouse grounds in Columbia – while Greenville’s elected officials led the losing effort to keep the flag flying.

Greenville, frequently ranked highly among places to visit and retire to, is not so hospitable to people who aren’t white.

When Greenville’s African-American community raised the consciousness of white voters to their righteous call for recognition of the King Holiday, Not In Our Town was on the scene, recording the final, decisive years of effort to make that particular dream a reality. The result: an eight-minute NIOT production appealing for funds to produce a full-length documentary under the working title, “Holiday.”

The “Holiday” project didn’t get funded.

Some “veterans” of the King holiday campaign recently obtained a copy of the eight-minute “Holiday” video from NIOT. (I appear in it.) We thought that, after 15 years, a screening might help us recall how that campaign was successful. And it did… albeit in a surprising way. The film’s inspiring message of people from all walks of life coming together to uphold what’s morally righteous struck us as being very timely. “Holiday” is not the dated quasi-historical account we were prepared to view.

Dr. King himself told us why “Holiday” endures. King often reminded his audiences that the arc of the moral universe bends toward justice. He never prophesied that it will make contact. It probably can’t – but it can always get closer.

I liken this to the view from the crow's nest of a tall ship. As it sails toward the horizon, the view is ever-changing with new discoveries and revelations along the voyage – yet the ship never gains as much as one inch on the horizon it sails toward.

The inability to cross the finish line can be discouraging.

This paradox of perpetuity must be especially vexing to a filmmaker who has to identify both a beginning and an end for a documentary.

Without a finish line to cross, when does the story of “Holiday” end? Or, for that matter, begin?

For Greenville, our next chapter may very well begin in 1960…or earlier.

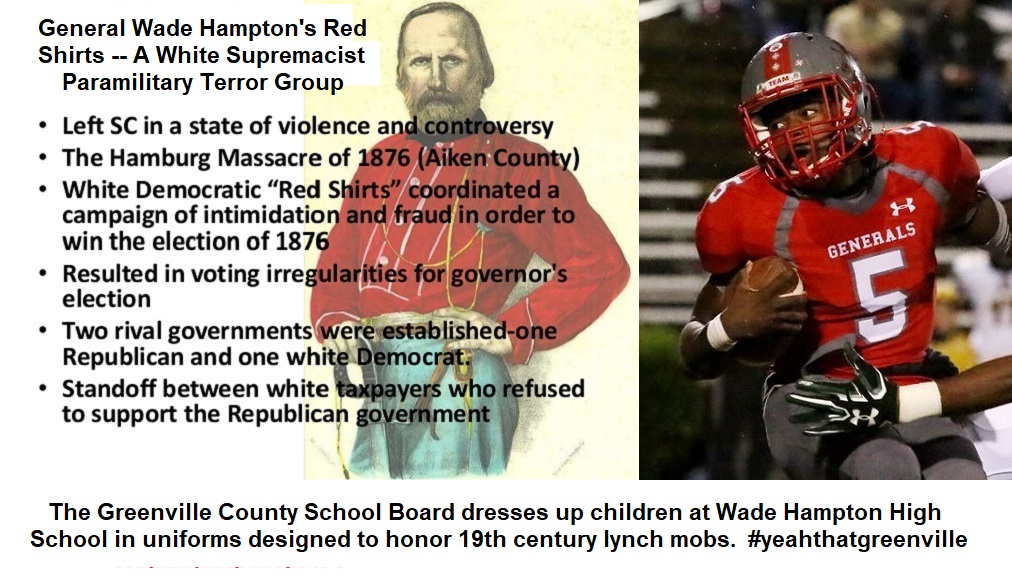

In 1960 – after Little Rock had desegregated – Greenville christened a new high school for white students only. It was given the name “Wade Hampton” – for a Confederate officer from Greenville who mostly made a name for himself after the Civil War when his paramilitary group of “Red Shirts” lynched some 150 Freedmen in the state to intimidate all African-Americans who might consider exercising their newly-won right to vote. In the wake of the Brown v. Board of Education decision, South Carolinians rediscovered the mostly forgotten Wade Hampton. Wearing a red shirt became a well-known way to declare support for segregated schools.

Wade Hampton High School still exists while none of the county’s all-black high schools survived desegregation as high schools. Worse, the school’s mascot is a general and the uniforms, in 2019, have children – including African-American students – dressed in red jerseys.

|

|

|

Indignities like this abound and are commonplace here – to the point where they’re invisible or they’ve gone on so long the patent racism is defended as a local tradition.

So, is “Holiday” a wrap – 15 years after Greenville’s County Council voted to recognize the King Holiday?

It seems not. There’s too much yet to fight for and the King Holiday was just one step toward an elusive horizon.

As the late James Shannon observes near the end of the “Holiday” short film, “That's how social change happens in this country. Nobody gives it to you. And it's incremental. It's one little step. One little piece. And unless you're willing to take that step, grab that piece, you're never going to get it."

Add new comment