by Jon Norton

This post was first published on WGLT.org and was published here with permission.

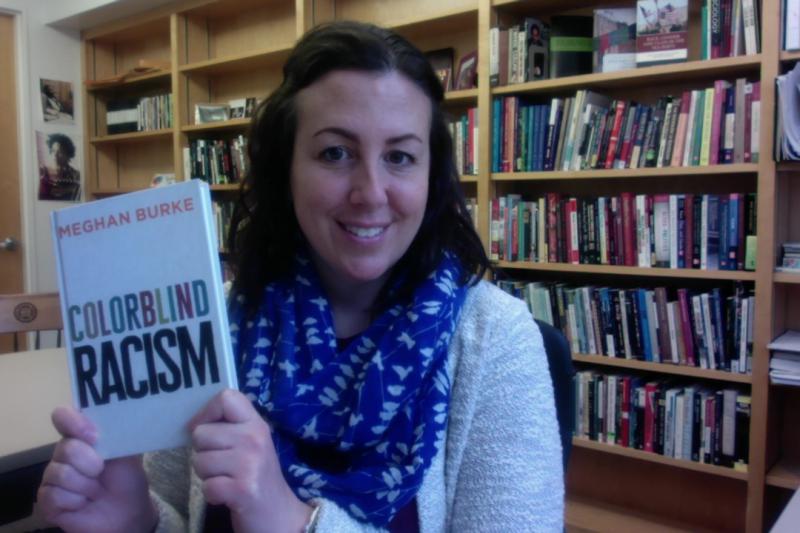

An Illinois Wesleyan University professor of sociology, Meghan Burke, says fighting against racism requires more than simply ignoring race.

Burke's latest book "Colorblind Racism" argues that the well-intentioned trend of “colorblindness,” or disregarding the importance of an individual’s race, does not lead to racial equality.

“The way I like to talk about colorblind racism is that it reflects a belief that racism is a thing of the past, and that any way we might understand what is clearly demonstrated perpetual persistent racial inequality in the United States is either explained by individual merits or lack thereof. Or what I say is what we imagine to be true about our own or each other’s cultures,” said Burke.

Rugged individualism is an attribute many if not most Americans see as the core of the country’s identity. That is, anyone who works hard enough can achieve nearly anything. Burke said that is a cherished ideal and society would be served well if merit, talent, and hard work was the only thing that mattered when advancing in society.

“I think for many white folks, it’s easy for us to assume that that indeed is all that is going on in shaping our successes or lack thereof,” said Burke. “What we’re less able to see for a variety of reasons are the ongoing realities of racial privileges, and the ways that our long history of overt and covert racism has shaped society in a way where individualism is simply not the only way we can understand how and why we still have segregated communities and persistent disparities in just about any measure of social outcomes in the United States.”

She said in a way, people don’t want to let go of the ideal that individuals alone are responsible for their success, and conversations stall when that becomes the only “common-sense” way of understanding persistent racism.

She also pointed to how covert racism is not a new phenomenon. For example, neighborhoods in the 1950s and 60s would often cite lower property values as a reason to exclude especially blacks. Burke said another example of colorblind racism dates to the late 1880’s and early 1900s.

“An example I often use with my students is the 1924 Immigration Act when we made a law that we were going to restrict immigration to the United States based on a flat percentage (2 percent) of any of the immigrants that were in the country in the 1880 census. That looks fair on the surface, but what makes that colorblind racism is that by the 1920s there was such extreme anxiety about a certain group of immigrants, in particular Asians and those from southern and eastern Europe. In the 1880 census, we had far higher numbers of western and northern European immigrants. So what that did by allowing an allegedly even percentage of immigrants in a ‘colorblind fashion’ really helped us to institutionalize racial preferences for immigrants from northern and western Europe,” said Burke.

Read: more desirable Europeans.

In addition to housing and immigration, institutionalized racism in the United States has manifested itself in policing, education, and voting. Somewhat surprisingly health care is not immune to colorblind racism. Burke said unevenness in availability to seek quality care was one example. That is, those with jobs that don’t allow access to either affordable or quality health care.

“There’s also plenty of well-meaning medical practitioners who still carry assumptions about even things like pain tolerance,” said Burke. “There have been studies that indicate doctors, nurses and other professionals may assume black folks have a higher pain threshold and may be less likely to trust their own narratives about their bodies and the pain they’re experiencing. It can often carry with it assumptions about behaviors that may signal healthy or unhealthy behavior and willingness to be able to provide certain kinds of care and response to that.”

Colorblind racism acknowledges the stickiness of how white privilege continues to permeate most American institutions. But what is the motivation for those who benefit from that privilege to help tear down walls that prevent marginalized groups from accessing “the American dream?”

“That’s a great question and in some ways I’m spoiled,” said Burke. “The shortest amount of time I have is three full days to work with students. I write books about this I get to spend years on. But I think in passing conversations it’s more challenging.”

The question also signals racial apathy, that is since it doesn’t affect someone personally, why should they care.

“I think that is beginning to be a harder position to hold as movements do the good work of helping us recognize the realities of ongoing racism and bias,” said Burke. “Seeing it as a life and death matter for example as the Black Lives Matter groups have done, and movements long before it also have. I think we have to be able to recognize people’s shared humanity and the common goals many of us have across the political spectrum. And to speak to peoples best selves and the people they want and need to be. This is what makes society complicated as society is never going to be uniform.”

Burke’s book “Colorblind Racism” is available in print and e-book formats and other websites. There was a community event related to the book held at the Normal Public Library on April 1. It's co-sponsored by Not In Our Town and the Black Lives Matter Book Club.

Add new comment