By Dr. Becki Cohn-Vargas

Not In Our School Director

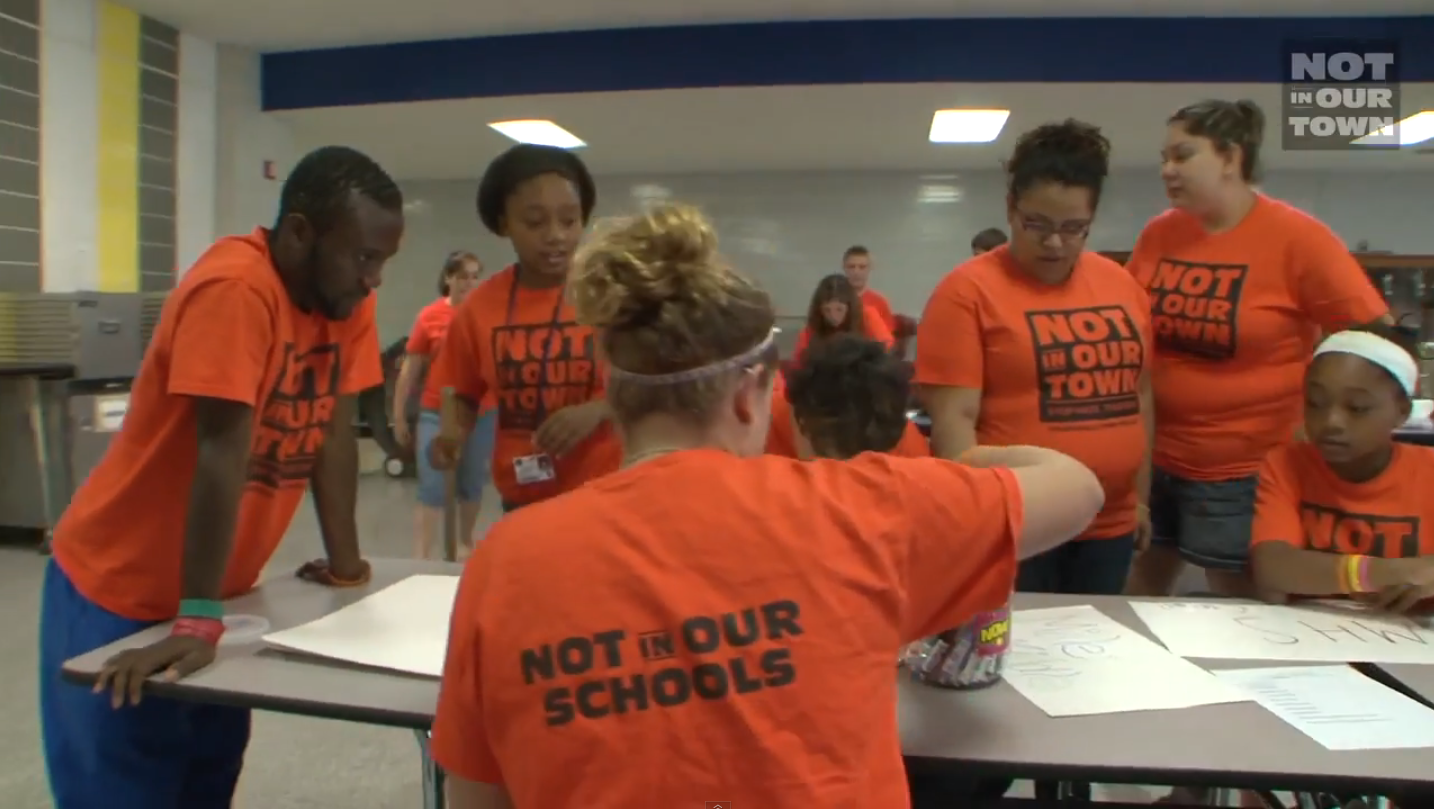

In a recent NIOT blog, we shared how student leaders from the Not In Our School anti-bullying campaign at Marshalltown High School in Iowa were the ones who spoke up and averted a school shooting. In this four-part series, we will explore the issues of school violence, show one elementary school's activities to stop school violence and offer a two-part exploration of the restorative justice model, a promising strategy for interrupting and ending cycles of violence.

Youth Violence

Adults distinguish between brutal teasing, bullying, fighting, and a school shooting, but all these behaviors are part of a continuum of youth violence. Behaviors on this continuum can easily escalate.

The Center for Disease Control (CDC) considers youth violence a public health issue. In 2010, 4,828 young people ages 10 to 24 were victims of homicide—an average of 13 each day.

In a 2012 nationally-representative sample of youth in grades 9-12, the CDC reports that:

• 32.8 percent reported being in a physical fight in the 12 months preceding the survey; the prevalence was higher among males (40.7 percent) than females (24.4 percent)

• 16.6 percent reported carrying a weapon (gun, knife or club) on one or more days in the 30 days preceding the survey; the prevalence was higher among males (25.9 percent) than females (6.8 percent)

• 5.1 percent reported carrying a gun on one or more days in the 30 days preceding the survey; the prevalence was higher among males (8.6 percent) than females (1.4 percent)

Violence has far-reaching effects on all parties: perpetrators, victims, and those who are exposed to violent acts. Youth often develop PTSD and have higher risks of mental health issues, substance abuse, and suicide. Cycles of violence perpetuate themselves. Early violent behavior has been found to lead to later problem behaviors in adulthood.

The NIOS principles for preventing bullying and intolerance, can also be applied to preventing all forms of violence:

1. Teach bystanders to be upstanders who speak up and stand up for others in a safe way.

Students know when big fights are about to break out and they often know when a student is planning to bring a gun. They need to learn ways to safely intervene and tell their peers to stop and when to get help.

Students know when big fights are about to break out and they often know when a student is planning to bring a gun. They need to learn ways to safely intervene and tell their peers to stop and when to get help.

2. Let students lead the way.

Students don’t want to be lectured. They want to be involved in identifying the issues and the solutions. Students respond when their peers play a leadership role.

3. Create identity safe school communities where students, whatever their background feel accepted, valued, and included.

An identity safe school climate is a sustained effort to teach positive social skills, promote empathy and kindness, and positive relationships and understanding across all forms of difference.

4. Get the whole community involved.

All of us, from educational leaders, to parents, youth and the entire community must work together to end school violence.

The good news is that the CDC reports that these efforts do work! In the next blogs, we will share some promising strategies.

Information from the CDC

CDC Best Practices of Youth Violence Prevention — A Sourcebook for Community Action Best

The UNITY Policy Platform describes what needs to be in place on the ground in cities to prevent violence, and delineates the supports cities need for their efforts to be successful and sustainable.

Minneapolis Blueprint for youth violence prevention has resulted in significant reduction in youth violence.

Add new comment