By Rachel Burke Koslofsky

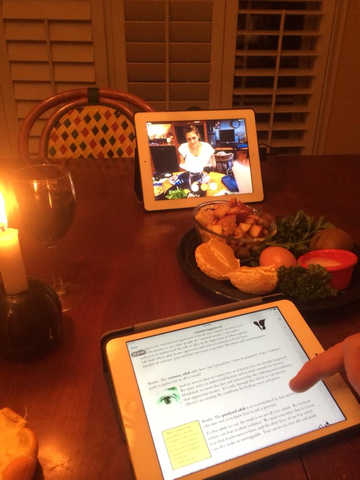

Last Monday, I led our family’s Second Annual Interfaith Skype Passover Seder. At 6 p.m. California time and 9 p.m. Kentucky time, each segment of the family crowded around a computer screen to participate. This offbeat tradition was born out of an experimental seder set in Kentucky during Holy Week of 2012—and fueled by curiosity.

Last Monday, I led our family’s Second Annual Interfaith Skype Passover Seder. At 6 p.m. California time and 9 p.m. Kentucky time, each segment of the family crowded around a computer screen to participate. This offbeat tradition was born out of an experimental seder set in Kentucky during Holy Week of 2012—and fueled by curiosity.

My father’s parents raised him as a Brooklyn Jew in the 1950’s. During the same decade, and just 700 miles away, my mother grew up in the Christian Church in Maysville, Kentucky. It might as well have been another world. My father’s childhood was full of pastrami sandwiches on rye and his Zadie’s most perfect challah. My mother’s consisted more of honey glazed ham and butterflake rolls from the family bakery her grandfather and Uncle Sam ran in Danville, Kentucky. My father also grew up with an Uncle Sam, three in fact, though prior to their arrival at Ellis Island they were Uncle Simcha, Schmuel and Shlomo. But that was back in the shtetl of Lithuania. The one thing the two did have in common growing up was their fathers’ dedication to their respective faiths.

When my parents married on Stinson Beach in Northern California 32 years ago, my grandfather made a toast to his daughter and new son-in-law saying that “just like the road to the beach they stood on, the road to their marriage had also been long and winding.” What he was referring to was the union of two very different cultures at a time when the mixing of differences was still quite radical.

This year, on April 13, three residents of the Kansas City, MO-area were shot and killed. Reat Underwood, 14, and his grandfather, Dr. William Corporon, 69, were gunned down in the parking lot of the Jewish Community Center on their way to a singing competition. Teresa “Terri” LaManno, 53, was shot and killed after visiting her elderly mother, who suffers from dementia, at the Village Shalom living center. The alleged suspect, Frazier Glenn Cross Jr., is a known racist and former member of the Klu Klux Klan, according to the Kansas City Star.

Some people wonder whether it matters that this incidence of violence indeed qualifies as a hate crime. Yes, three people were shot and killed on the premises of Jewish facilities, however, none of the victims were, themselves, Jewish. This incident raises the question: Would our response to this act of violence have changed if the victims had been Jewish? Are our lives not irrevocably intertwined with one another? We all wear prejudice and discrimination on our sleeves, yet we would be wrong to think that we can read the complexity of another human being from their exterior, as Cross did on April 13.

Within last week’s virtual Passover Seder, I strove to address some of these issues at hand despite the difference in our two groups’ origins, both physically and spiritually. Passover is a Jewish holiday that essentially celebrates the liberation from slavery of the Jewish people.

Over the years, there have been a few additions to our seder plate. An orange to symbolize the fight for gender equality in Jewish life, a bowl of olives for our hopes of peace among Israelis and Palestinians. This year we added an artichoke. This was an idea that stemmed from Rabbi Geela Rayzel Raphael of interfaithfamily.com, who describes an artichoke as having “many petals, with thistles and a heart,” much like the Jewish people. I would push this description to encompass not just the Jewish people, but a spectrum of different faith communities. Jews represent just one “artichoke petal” of the many that the vegetable dons.

Over the years, there have been a few additions to our seder plate. An orange to symbolize the fight for gender equality in Jewish life, a bowl of olives for our hopes of peace among Israelis and Palestinians. This year we added an artichoke. This was an idea that stemmed from Rabbi Geela Rayzel Raphael of interfaithfamily.com, who describes an artichoke as having “many petals, with thistles and a heart,” much like the Jewish people. I would push this description to encompass not just the Jewish people, but a spectrum of different faith communities. Jews represent just one “artichoke petal” of the many that the vegetable dons.

We can also apply the metaphor to the great diversity within the Jewish community itself. Too often, we forget to, as Rabbi Raphael poetically states, “let the thistles protecting our hearts soften so that we may notice the petals around us.”

The artichoke on the seder plate serves as a call for openness and interconnectivity among the spectrum of faith communities that our society holds. We will never know what lies at the heart of each others’ communities if they are always guarded with thorns.

During my grandfather’s ministry, he would record daily “dial-a-devotionals” that consisted of a piece of scripture, a message and a prayer that were made accessible to the public by dialing a phone number anytime they chose. They were particularly intended for those who were homebound or hospitalized or sought anonymous spiritual support. Our Interfaith Seder concluded with the following devotional from my grandfather, Dr. M. Glynn Burke, former pastor and theologian.

“The scripture says, ‘And Jesus looked around at them with anger, grieved at their hardness of heart.’ (Mark 3:5) One test of a person’s character, the quality of his spirit and life is this: What are the things that make him mad?...Some people get angry only at slights and insults to themselves personally. The real short-coming of most of us is that we get angry, but we get angry at the wrong things. Jesus, on the other hand, became angry at injustices inflicted on other people. He was angry because of human suffering or lack of concern for that suffering…Grant, O God, that we may get angry at the right things. That we may feel the noble emotion of indignation because of wrong-doing and suffering. Amen.”

May this serve as a reminder to soften our hearts in memory of Reat Underwood, Dr. William Corporon, and Teresa “Terri” LaManno.

Rachel Burke Koslofsky is a member of the Not In Our School team and Bay Area native. She also works with youth leadership and cultural exchange programs based in the Bay Area and South America. You can also find her in the kitchen, reading a book of short stories or trotting around with camera in hand.

Add new comment